Tags

art, autobiography, childhood, Creativity, finger painting, Medicine, memoir, memories, Psychiatry, Psychology, self-making, Therapy

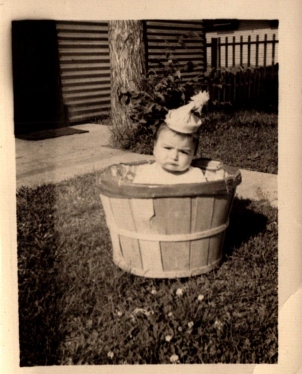

Childhood

Childhood

My own journey with creativity started in Kindergarten with finger-painting. I can remember the smell of the newsprint paper and finger paint as pungent, oddly enticing, and stimulating.

The experience of putting my fingers in the cold gel paint and smearing the colors over a large piece of paper charged my young mind with a sense of freedom, excitement, and tranquility. I would go into a trance-like state, almost euphoric, during painting sessions. It was my favorite activity. Unlike other kids that form an attachment to a teddy bear for self-soothing—a transitional object—my art making tools became my way to self-soothe.

I vividly recall winning praise from my teacher, Miss Eads. She was my first ‘dream-girl’, so when she admired my handiwork, it embellished my art-making with romance. Winning her attention empowered my imagination to take risks, to be inventive, and show off what I could do. I was especially aiming to please her.

I always made art in grammar school, and I became known as ‘the class artist’ by third grade. At home, I loved spending time building plastic models and painting them—especially Knights in shining armor, and Monsters from the cinema. I began collecting the classic Horror films in 8mm and would create dioramas with the models. My creativity soared, cutting across all media. Little did I realize that each of these experiences with creativity helped my emotional self-regulation during times of personal and social stress.

My creative urges also translated into intellectual interests in the classroom. In our creative writing, I could whip up an essay out of my art imagination effortlessly—storytelling became another art-form.

We now have knowledge from developmental neuroscience that reveals the importance of cultivating and supporting our inborn creativity during childhood. Creativity is a natural human trait—the first practices of our wonderful capacity for creating abstract, symbolic, communication. As children, we begin integrating all our sensory modalities for creativity through singing and speaking, story-telling, image making, dancing, and acting-out in play.

When a child’s world feels secure, the excitement stress during creative play strengthens the capacity for a healthy sense of authenticity—a ‘true self’. We also empower our creative resilience to stresses in later life.

When the stress of life overwhelms a family’s ability to provide security, the child’s capacity for functioning and growth is compromised. The resilience to stress in the future can also be undermined.

We see this in the millions of refugee families across the globe. It is critical for societies to support families to stay connected as they go through these horrible experiences. We are amazingly capable of surviving and recovering from traumatic situations when we stay creatively connected to each other.

In future blogs, I’ll explore ‘brain/mind autopoiesis’ across the life cycle with science and my own experiences.

Featured photo of painting of handprints by Bernard Hermant on Unsplash

Photo of Dr. Romero as a child from family archives